Washington —

The number of madrassas, or religious schools, has increased fourfold under the Taliban in Afghanistan as experts worry that the rise could fuel extremism in the country and limit opportunities for younger Afghans, particularly girls.

“In the past year, at least 1 million children have been enrolled in madrassas for religious education,” said Karamatullah Akhundzada, the deputy minister of education, in a September news conference.

The year’s new enrollments brought the total to 3.6 million students at more than about 21,000 madrassas registered in the country,

This shift marks a change in the educational landscape in Afghanistan, where madrassas now outnumber the more than 18,000 public and private schools.

Jennifer Brick Murtazashvili, founding director of the Center for Governance and Markets at the University of Pittsburgh, told VOA that the increase in the number of madrassas is part of the Taliban’s effort to establish control.

“It’s important to look at madrassas together with local governance. Under the republic [former Afghan government], there was no formal village governance, but the Taliban have replaced that with religious leaders who now hold local power,” Murtazashvili said.

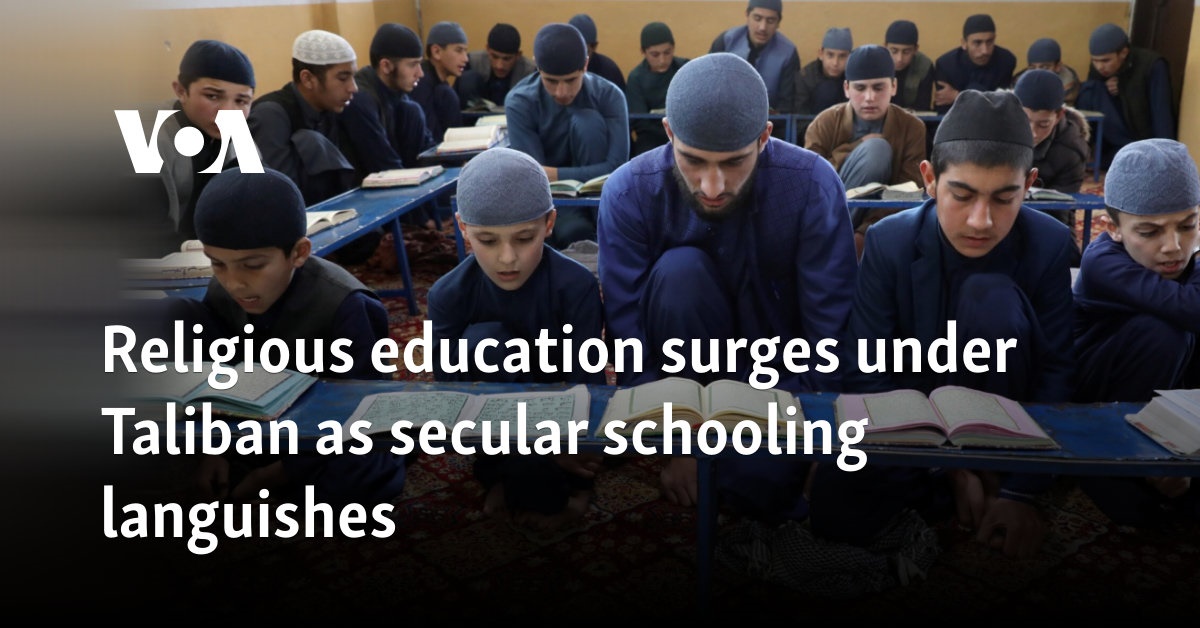

FILE – Afghan children hold the Quran as they go to a madrassa, or religious school, in Dand Ghori district in Baghlan province, Afghanistan, March 15, 2016.

Before the Taliban seized power in 2021, there were about 5,000 madrassas registered across Afghanistan.

After returning to power, the Taliban aimed to transform the education system.

Officials at the Taliban Ministry of Education said they have taken steps to “revise and reform” textbooks and curricula in the schools in the past three years.

Before the Taliban, more than 9 million students were enrolled in all types of schools, with 39% of them girls.

Following the Taliban’s return to power, the group imposed a ban on girls’ secondary education, making Afghanistan the only country in the world to restrict girls from attending secondary school.

The Taliban ban on secondary education deprived about 1.5 million girls of going to school.

Murtazashvili sees the ban on girls attending school beyond the sixth grade as a clear sign of extremism.

“By robbing girls of education, they are robbing the country of its future,” Murtazashvili said, adding that “you’re not going to have a future of women nurses and doctors. You’re going to see mortality increase.”

One young woman who spoke to VOA but did not want her name used was in 11th grade when the Taliban took power in 2021 and banned secondary education for girls.

She said she enrolled in a madrassa in Herat City, hoping to continue her education, but was “disappointed.”

“At first, I thought I could learn and reconnect with friends, but it felt more like brainwashing,” she said, adding that “they kept telling us education wasn’t for us. We should become good housewives and give birth to future Islamic leaders.”

After three months, “disheartened with the restrictive environment,” she quit the madrassa.

FILE – Afghan girls attend a religious school in Kabul, Afghanistan, on Aug. 11, 2022.

Mohammad Moheq, former Afghan ambassador to Egypt and author of many books on Islam and Afghanistan, told VOA the Taliban push their strict interpretation of Islam through these madrassas.

“Their goal is to stop people from thinking for themselves and push their strict version of Islam that fits their political agenda,” Moheq said.

Madrassas played an important role in the Taliban’s rise to power in the late 1990s as many of the Taliban were graduates of madrassas in neighboring Pakistan.

In April 2022, the Taliban announced their plan to open three to 10 new madrassas in every district in Afghanistan.

“Religious sciences should be further taught throughout Afghan society,” said Noorullah Mounir, the then-minister of education, as he urged Afghan teachers to instill an “Islamic belief” in their students.

Saba Hanif, a professor at the University of Education in Lahore, Pakistan, told VOA that there is a need for the international community to talk to the Taliban to find “a middle ground” and blend religious and “worldly” education.

“They should agree on certain terms and show the Taliban how purely religious education could harm the country’s future, particularly in terms of job opportunities and economic growth,” Hanif said.

She added that if children are exposed to “only one way of thinking and one way of living life,” it will perpetuate extremism.

“This will be quite obvious. And it could be very dangerous for the region because, you know, of their past practices. They try to force it on others, and they also don’t hesitate in using power to control others,” Hanif said.