A few years ago, professor Khaled Abou El Fadl was visited in his home in Los Angeles by an antiquities dealer. “He offered me a gift that I hate to see,” he told New Lines. “A page, a single page, from a manuscript.”

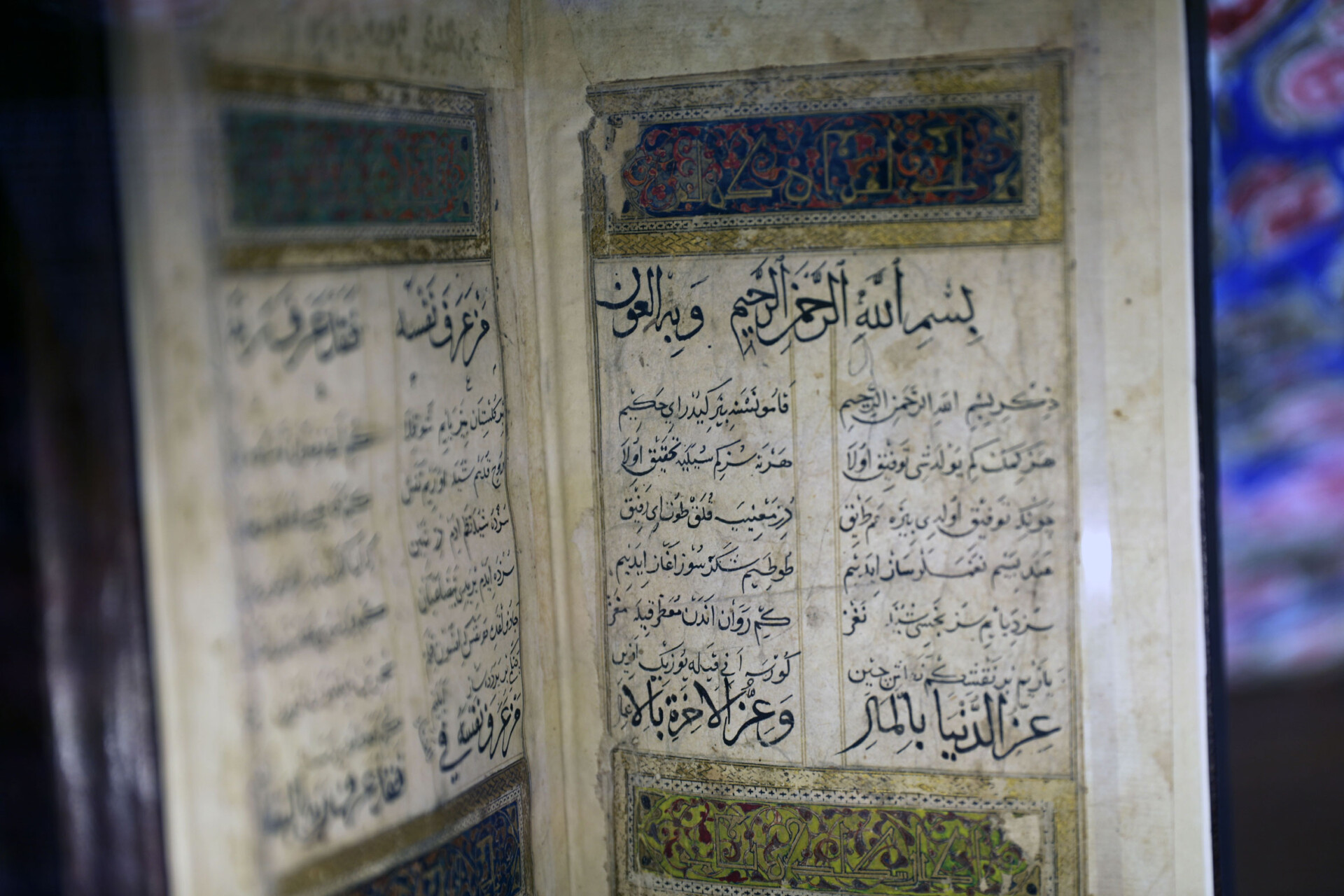

One of the most egregious acts of violence against a manuscript, short of burning it completely, is to rip it up, yet this is what happens to many historical books, especially the most richly illuminated examples, because there is far more money to be made by selling them off page by page than by keeping them whole. People may treasure the pages for their imagery, perhaps framing them as art, but this practice destroys part of their historical value. We can no longer understand the work as a whole, either its content or the details it provides about its history, such as references to the scribes or previous owners; material features that tell us about the cultural and professional milieus in which the object was produced; or the marginalia often scattered throughout a text which give insights into teaching, studying and commentary practices.

After this show of destruction, meant as enticement, the dealer showed El Fadl a list of what he was offering for sale: a catalog of over a hundred manuscripts and books. El Fadl knew at once that the whole list was from Timbuktu, which used to have one of the most impressive collections of manuscripts in Africa. When the heritage was threatened by the arrival of extremists in the area in 2012, there was a scramble to preserve the valuable books and manuscripts that were held in the city, many of which are unique. Efforts were made to smuggle some to the capital of Mali, Bamako, while others were salvaged by keeping them within family libraries in Timbuktu. Others were taken by local tribes who knew their value, and so buried them in the desert — a very good environment for preservation, unless looters get wind of the location.

“This agent was somehow connected to some folk there who dug out the manuscripts from under the sand,” El Fadl said, with evident frustration. “He was offering to sell me the entire collection for $100,000.” The catalog had short descriptions for each work, which showed the immense historical value of what was in his possession. “There were books on Maliki law, by sub-Saharan African Maliki scholars I’d never heard of,” said this eminent scholar, well-versed in Islamic law and history. “The list he showed me, with philosophy, travel, law — it blew my mind. One of the most amazing on the list was a Muslim writing in the 18th century about the slave trade. Imagine what an insight that text could give us.”

The dealer of this collection was confident he was going to sell it, bragging of his connections to universities in Israel, the U.K. and the U.S. He conveniently omitted the legal implications of exporting and selling possibly looted materials, which are either entirely forbidden or regulated in each of those countries. The U.S., in particular, has tightened its grip over the import of illicitly trafficked cultural objects that enter the country from abroad, with the Antiquities Trafficking Unit in New York leading the way in tracking down smuggled objects.

For a scholar like El Fadl it could be extremely tempting to buy, despite the potential illegality of how the documents were acquired, but it is by no means a straightforward decision. Research shows that buying historical manuscripts and objects, however well-intentioned it may be, leads to the opposite of the preservation of history for which El Fadl is striving. It has been shown to encourage the trade in artifacts, financing and incentivizing those responsible for the illegal export and dispersal of heritage. Ultimately, this strategy risks creating more situations in which sites are looted, libraries or museums become targets, or vulnerable members of local communities are exploited in illegal digs.

“So do I refrain from buying the manuscript in order not to encourage this type of trade?” he asked us, “Or do I risk that a valuable manuscript would be lost to history?” El Fadl is, at bottom, a scholar. “These manuscripts should not be in museums, they should be available to scholars to edit, publish and study.” And he knows that the dealers are very much not scholars. “The worst of it is that manuscript traders will simply discard the manuscripts that they cannot sell.” It is impossible to know just how much has been lost to history for want of a market, but it is known that it has happened for centuries — perhaps as long as manuscripts have been produced. Yet supporting the sellers with sales means they will carry on their habits, including throwing out things they can’t shift. “It’s like being between a rock and a hard place,” as El Fadl put it. In this case, there was no temptation, as the collection was being sold as a job lot for $100,000 — some would say way below its real value, but still too high for a jobbing academic. Furious at the loss of such priceless insights, El Fadl showed the dealer the door.

The trade in historical artifacts is ancient, and of course not always pernicious; expert collectors and institutions have often served as protectors of heritage, preserving, documenting and researching items in their possession for posterity. But El Fadl and others believe that what is happening at the moment, powered as it is by numerous online marketplaces that are proving very difficult to police, is unprecedented.

The advent of social media has made it much easier to sell objects of dubious provenance (that is, objects that do not have a documented chain of ownership tracing their story). It has also multiplied the sales of fakes to inexperienced collectors. New platforms and strategies are emerging all the time, making it hard for law enforcement to keep up. Recent conflicts across the Middle East have created conditions in which the hunger for historic artifacts and manuscripts can be amply supplied by stolen and looted items. Because of the sheer scale of the market, and the real repercussions on people’s lives — including the role of organized crime, the exploitation of cheap labor, the violation of individual and national property rights, the damage to the heritage and resources of local communities and the loss of historical understanding — the illicit trafficking of antiquities needs to be taken seriously, by all.

“I have seen a single page from a 14th-century manuscript on geography, from Iraq,” El Fadl said, “and there are only three extant copies of that work that we know about. That means one out of three copies in the world has been ripped up.” He has a shrewd idea that it’s the copy from Baghdad University, one of thousands and thousands of manuscripts that went missing after the invasion in 2003.

“I’ve met Iraqi university professors who told me horrors of what happened to the manuscripts in their country,” El Fadl continued. One came to visit his department at the University of California, Los Angeles, and described how he had tried to convince American forces to protect the libraries from the pillaging that he could tell was coming from the sheer desperation on the streets. “Ultimately, the U.S. forces told him, ‘We’re not here for that — you’re telling us to worry about books when we’re trying to keep our soldiers alive?’” This Iraqi professor, together with a friend, picked out the most valuable 10 and kept them at home, but they couldn’t do anything about the rest: Many have disappeared entirely, others pop up on the black market.

It’s not just manuscripts that are on sale on platforms like eBay. Among the many objects El Fadl profiles are Islamic golden coins, advertised as minted in Syria, Iran and Iraq in the Umayyad period in the seventh and eighth centuries. These small gold items, bearing Arabic inscriptions — “irreplaceable, beautiful, gorgeous pieces of art,” in the words of his video — are sold for less than $2,000; copper coins are much cheaper. And it’s trivial to find many more examples with a quick browse on eBay.

According to recent research by the archaeologist Neil Brodie, there was an increase in the sale of Umayyad copper coins from Syria after 2011, showing the impact of the conflict there, when many factions engaged in the sale of antiquities, most notoriously the Islamic State group. Brodie focused on a beautiful and rare type, bearing the stylized portrait of (probably) the caliph Abd al-Malik and usually called the “Standing Caliph.” It was in circulation only briefly in the late seventh century and is changing hands again today, online.

Example of a “Standing Caliph” coin, dated 696/7. (Ashmolean Museum/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

Researchers think that the increase in illicit sales of such small, pocketable artifacts in recent years is related to the ease of internet sales. On eBay, for example, there is a seller who seems to specialize in Roman glasswork, advertising an “early Islamic glass vessel pot” from Jericho, in Palestine, among other such items. The same seller has small mosaic stones, known as tesserae, on offer, dating from late antiquity and coming from al-Khalil or Hebron, also in Palestine, in the occupied West Bank. The description on the website does not provide any information about the objects’ provenance or ownership chain. There are so many red flags, but information is lacking, and requests for more information go unanswered. Where were these glass objects found exactly? If they were found during regular archaeological excavations, why are they being sold on the internet? How was the seller able to acquire them in the first place?

These references to Jericho and Hebron ring particular alarm bells. The West Bank was split into different administrative regions after the Oslo Accords were signed in 1993, meaning there is now a patchwork of regulations concerning the protection of cultural heritage in Palestine, which researchers like Morag Kersel have shown has facilitated the trafficking of antiquities despite the existence of regulations to curtail it. More typically, however, such sellers promote their merchandise as coming from less specific areas, such as “the Middle East,” and promise to ship them safely from third countries, like Thailand, or the U.K., where antiquities dealers are often based. While eBay states on its website that by policy “looted or stolen goods can’t be sold on eBay” and provides instructions and resources to sellers, in practice the burden of making sure that what they buy is licitly sold is on the buyer’s shoulders. What is the object’s life story? What laws allow for the sale of archaeological remains? Can they be exported legally? Can we rule out that they were stolen? Can we exclude the possibility that they are fake? We asked these questions to two different sellers of Middle Eastern heritage on eBay and there was, at the time of writing, no reply. No buyer can be sure of the legality of buying their objects.

The conflict in Syria, just as in Iraq, has led to widespread looting. Roman tesserae from here, too, have been found for sale, on Facebook. Because they are small and broken from a bigger whole, they are transportable, less traceable and more affordable — like single pages of manuscripts, or coins. Videos have circulated of Israeli soldiers rummaging in archaeological museums and storage facilities in Gaza during this conflict; no one knows where or when any items that were taken will next resurface. Perhaps they will be kept in soldiers’ homes as trophies of war, or soon be found on eBay, being sold for profit.

In a number of countries, Facebook has even been used to organize illicit archaeological digs and sell any objects discovered in such looting. In one post, a user gave instructions about how to loot a Roman tomb in Egypt; in another, users are able to place an “order” for specific looted “materials.” There is a lot of archaeological expertise in the region that on occasion fuels the illicit trade in antiquities: In a study in Palestine in the early 2000s, Adel Yahya showed that looters are often well aware of archaeological concepts and digging techniques: When archaeologists train their staff, they may be training future looters. Yahya writes that one of the grave diggers he talked to, an old man from the village of al-Jib, told him, “The people of the village learned digging and stratigraphy from [American archaeologist James] Pritchard who excavated the village in the 1950s.” This is another sign of the range of actors that can be involved in illegal digging, from villagers to soldiers, armed militias and archaeologists’ trained staff. In some communities, it is children who are often put at risk by being employed in dangerous digs, as cultural heritage expert Monica Hanna has shown in Egypt.

We asked El Fadl whether he ever found out who was selling the manuscripts and he came up with two very telling examples. The first was a professor in Lebanon. “He noticed that I had made these videos, and one of the manuscripts I showed was one he was selling.” The seller clearly noticed El Fadl’s attention, because “He began including letters purporting to be from the Lebanese government,” El Fadl said, “saying that they are aware this professor is selling this manuscript, and while it is important, they have determined that there are so many copies of this one there is no national loss.”

They were dealing with the wrong professor. “Either the letter is faked or he bribed someone,” El Fadl told us bluntly. “Unless you think the people in the Lebanese government are idiots, which is entirely possible, too. There is just no way that there are so many copies of this text that you can afford to let one out of your country.” In fact, the justification that selling a country’s cultural objects is licit as long as there are many similar copies in existence is entirely ungrounded. It does not reflect how institutions and experts operate today when deciding on acquisitions. In Lebanon there is an absolute ban on the export of antiquities and export licenses are required to bring abroad any kinds of objects in the category of cultural property. The story sold by the dealer to entice the collector was far-fetched, as El Fadl suspected.

His second example was a unique letter written by Mohammed Abdul Wahhab, who founded Wahhabism. “A heretofore unknown letter; I couldn’t find a record of it, anywhere,” El Fadl said. He tracked down the owner, a retired professor of Arabic at Dartmouth College. El Fadl spoke to this professor on the phone, and heard that there was proof the letter was authentic and that the contents were fascinating. “He was like 90 years old, living alone after his wife passed away.”

This professor had amassed a large collection when he was in Egypt in the 1970s and bought manuscripts on the black market, bringing them to the U.S. despite Egyptian laws, including this letter from Wahhab along with the chain of ownership proving its authenticity, suggesting it was first given to an Egyptian adviser to Wahhab, and then passed down through his family.

The professor explained to El Fadl his reasons for selling. He was worried about his manuscript collection when he passed away. He had sold manuscripts in the past when he really needed the money, he explained, which was not the case now, but Dartmouth library didn’t want them — they don’t have any Islamic manuscripts already and they weren’t interested in starting a new collection.

There are scholars and collectors all over America — indeed all over the world — who would jump at unique letters from such an influential figure in Islamic history. But acquiring rare books and documents like this is not as easy as one might think. Perhaps the professor couldn’t find a buyer because they suspected his collection would be a mixed blessing: Libraries are bound by the same legislation to tackle smuggling and illicit exports as other institutions, and many are no longer willing to acquire cultural objects without a proper paper trail showing provenance. Perhaps this particular document seemed odd or improbable. The professor hasn’t answered the phone since. Given his age, El Fadl is worried, but there are so many other manuscripts on his mind — this is just one of many stories of loss.

These two eBay sellers are each representative of how this trade has operated in the Middle East for centuries: the insider slowly dispersing library collections in the region, and the foreigner acquiring cheap manuscripts to take back home. Ahmed Al-Shamsy has written about how, in the 19th century, collectors drained the Middle East of manuscripts on all subjects and of all kinds, rare and ubiquitous, illustrated and not, old or new. The market responded, and items were acquired not only from legitimate booksellers but also from librarians and other employees of institutions, who quietly slipped them out for personal enrichment. El Fadl has personally seen manuscripts in Egypt with stamps identifying them as originating from a library, sometimes Al-Azhar, sometimes Dar Al-Kutub — both prestigious and ancient institutions of learning, both being illegally plundered for personal gain. One seller was an employee at Al-Azhar, and his responsibilities included librarian of manuscripts. That is, the custodian of an ancient center of learning was privately dismantling the collection he was paid to protect.

Initiatives have sprung up to combat this issue. For example, a project called “Himaya” (“protection” in Arabic), based at the Qatar National Library and supported by the International Federation of Library Associations, trained librarians and other professionals in the field to fight against the dispersal of books and documents from the Middle East and North Africa. The project tackled the same kinds of illicit activities that El Fadl is a witness to: libraries being damaged or depleted because of their own staff’s lack of awareness.

In July 2023, a team of librarians and conservators based in Gaza, together with staff from the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library (HMML) and the Endangered Archives Program, completed the digital preservation of more than 200 manuscripts in the collection of Gaza’s Great Omari Mosque, as well as books from the private collection of the scholar Abdul Latif Abu Hashim. The salvaged digitized collection includes ancient works of Arabic poetry, theology and Islamic law, mostly dating from the Ottoman period, with some going back to the 14th century. It was just in time. The library of the Great Omari Mosque was lost when the building was destroyed by Israeli bombing in December 2023. Like some manuscripts, the building was a palimpsest, with the oldest layer dating back to the late Roman period, when a church stood in the same place; the earliest use of the mosque was from the very first century of Islam. Similar digitization efforts led by the HMML have been happening in Mali, preserving the history that the dealer who visited El Fadl in LA was helping to destroy; these digitized manuscripts can be read, including their marginalia. But digital copies will never be the same as the physical originals.

Academics are clearly on both sides of the battle to preserve heritage: On the one hand, they are routinely consulted for advice and help in combating smuggling, yet many have also been involved with notorious smuggling scandals. A famous example of the latter is the “Hobby Lobby” scandal that unfolded between 2010 and 2017, when a large number of ancient artifacts from Iraq were seized by U.S. customs, destined for the Green family’s Museum of the Bible, in Washington, D.C. (The Green family are the founders of the Hobby Lobby stores.) Roberta Mazza’s research on that story uncovered an international network of dealers, collectors, investors, and scholars involved in the acquisition and dispersal of those fragments, including the renowned professor Dirk Obbink, who came under scrutiny for the theft of Egyptian papyri from one of Oxford University’s libraries. A curator at the British Museum also managed to siphon off over 1,500 artifacts from its collection, over many years, before he was discovered. Many have not been traced. It’s big business, and some academics and curators get drawn in.

It’s simply too easy to sell privately, either through networks or online marketplaces, and international law has not kept up. And it needs to, not least because there is widespread evidence that the trade finances international crime. This was made clear during the Islamic State years, when antiquities from Syria and Iraq were sold to fund the organization, but it’s been happening for longer and elsewhere, as well. Armed groups, warlords, state forces and government officials have all been involved in antiquities smuggling. And it’s hard to regulate on an international level because smuggling by definition involves crossing borders into different jurisdictions with different laws. Experts call the illicit trade in cultural objects a “gray market” — it’s not always even illegal.

El Fadl has been observing one part of it, the online market, for over a decade, and has seen extensive changes in what is available online, mirroring the invasions and conflicts in the Middle East. “There’s just more and more. Ten years ago, all the listings of Islamic manuscripts on eBay might be a page or two. Now they go on forever. There are more and more shields, swords, helmets.” And it’s not just quantity. “The market has become more and more bold. There are truly rare works for $10,000 or $20,000, including illustrated Qurans — gorgeously illustrated and decorated. Where were these Qurans? How did they wind up on eBay?” We will never know who commissioned or owned or worshipped using these beautiful objects, losing insights into past practices of Islam.

El Fadl tries to tell people that you cannot have a future without preserving the past, but he feels like he is fighting an impossible battle. “Over the years, what is for sale has changed, and that means that many manuscripts have disappeared into private hands. We have no way of knowing what they are, or what will happen to them.”

Ultimately, the plundering of Middle Eastern and Islamic cultures is not a problem that can be solved by buying objects of dubious origin, even with the aim of protecting them. In fact, this can fuel the very practices on the ground that are supplying the illegally acquired artifacts. It can only be tackled in the long term by fighting these practices — both traders spotting an opportunity, and the academics, librarians and museum custodians taking advantage of their privileged access. From cheap single pages and pieces of mosaic to the most beautifully decorated (and exorbitantly priced) illuminated manuscripts, anyone with an eBay or Facebook account can own a piece of the past, no matter how it was acquired or to whom it really belongs, and with no responsibility of preserving it for the future. As El Fadl put it: “It’s a horrific scenario, and a direct assault on Islamic history and civilization.”

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.