(The Indian Express has launched a new series of articles for UPSC aspirants written by seasoned writers and erudite scholars on issues and concepts spanning History, Polity, International Relations, Art, Culture and Heritage, Environment, Geography, Science and Technology, and so on. Read and reflect with subject experts and boost your chance of cracking the much-coveted UPSC CSE. In the following article, Rahul Ranjan revisits India’s independence and partition.)

During World War II, India was pivotal to British defence strategies in the Middle East and Southeast Asia. The British government sought to harness India’s resources for the war effort while maintaining tight control over Indian affairs. Winston Churchill, who became the Prime Minister of Britain in 1940, was a staunch imperialist, reluctant to grant any real concessions to Indian demands for self-governance. However, within his War Cabinet, there was a division, with Sir Stafford Cripps representing the Labour Party’s more progressive stance, which favoured India’s independence.

In 1942, the Cripps Mission was sent to India, offering post-war self-determination (dominion status), but with conditions that included the possibility of provinces seceding from a future Indian union — implicitly recognising the Muslim League’s demand for Pakistan. Congress rejected the offer, leading to a total breakdown in relations between the British and Indian leaders. As the war progressed, British prestige was further undermined by Japan’s advances in Southeast Asia.

Meanwhile, international pressure, particularly from the United States, pushed Britain towards decolonisation. By the end of the war, Britain was economically weakened and faced mounting political pressure, leading to a shift in its policies. The Labour government, which came to power in 1945, was more inclined towards Indian independence, although still cautious about relinquishing full control.

This period marked the beginning of Britain’s retreat from India, culminating in the 1947 partition plan, which divided India into two independent nations—India and Pakistan. The partition was a direct consequence of the complex interplay between wartime exigencies, international pressure, and growing Indian demands for self-rule.

The Hindu-Muslim divide and the demand for Pakistan

The process of partition in India was fundamentally driven by the deepening Hindu-Muslim divide, which became apparent during various negotiations leading up to the transfer of power. The Lahore Resolution, adopted by the All-India Muslim League in March 1940, marked a significant turning point, seeking to elevate the status of the Indian Muslims from a minority group to a separate nation. It positioned Muhammad Ali Jinnah as the “Sole Spokesman” for Muslims, and the Muslim League’s demands became non-negotiable.

Jinnah’s rejection of the Cripps proposal exemplified his insistence on Muslim self-determination and equality with Hindus, rather than mere provincial autonomy.

As the Congress launched the Quit India Movement, the British found allies in Jinnah and the Muslim League.

Winston Churchill used the Hindu-Muslim tensions as a pretext to maintain British rule in India. During this period, the British actively supported Muslim League ministries in various provinces, further deepening the divide. Despite these developments, the demand for Pakistan remained ambiguous, focusing more on autonomy within a federal structure rather than outright separation.

Political negotiations and failures

Throughout the 1940s, Congress made several attempts to address Muslim demands through high-level negotiations. One notable attempt was the Rajaji Formula proposed by C. Rajagopalachari in 1944. The formula suggested a post-war commission to demarcate Muslim-majority districts, where a plebiscite based on adult suffrage for everyone, including non-Muslims, would decide whether they would prefer to join Pakistan.

However, Jinnah rejected this proposal, leading to the failure of the Gandhi-Jinnah talks in September 1944. The fundamental disagreement between Gandhi’s vision of a united India with some level of partnership and Jinnah’s demand for complete sovereignty led to a stalemate.

The issue resurfaced in 1945 when then Viceroy of India, Lord Archibald Wavell, attempted to form a coalition government involving both Congress and the Muslim League. The Simla Conference of 1945, convened to discuss the formation of an entirely Indian executive council, collapsed due to Jinnah’s demand for Muslim League’s exclusive claim to nominate Muslim members. Congress’s refusal to accept this demand, which would have confined it to representing only caste Hindus, further exacerbated tensions.

The Muslim League’s rise and mass mobilisation

During the 1940s, the Muslim League rallied widespread support among Muslims. This period saw the League’s transition from representing the landed aristocracy to gaining support from professionals, business groups, and religious leaders. The League’s campaign for Pakistan was not just political but also imbued with religious legitimacy, thanks to the support of leading ulama, pirs, and maulavis.

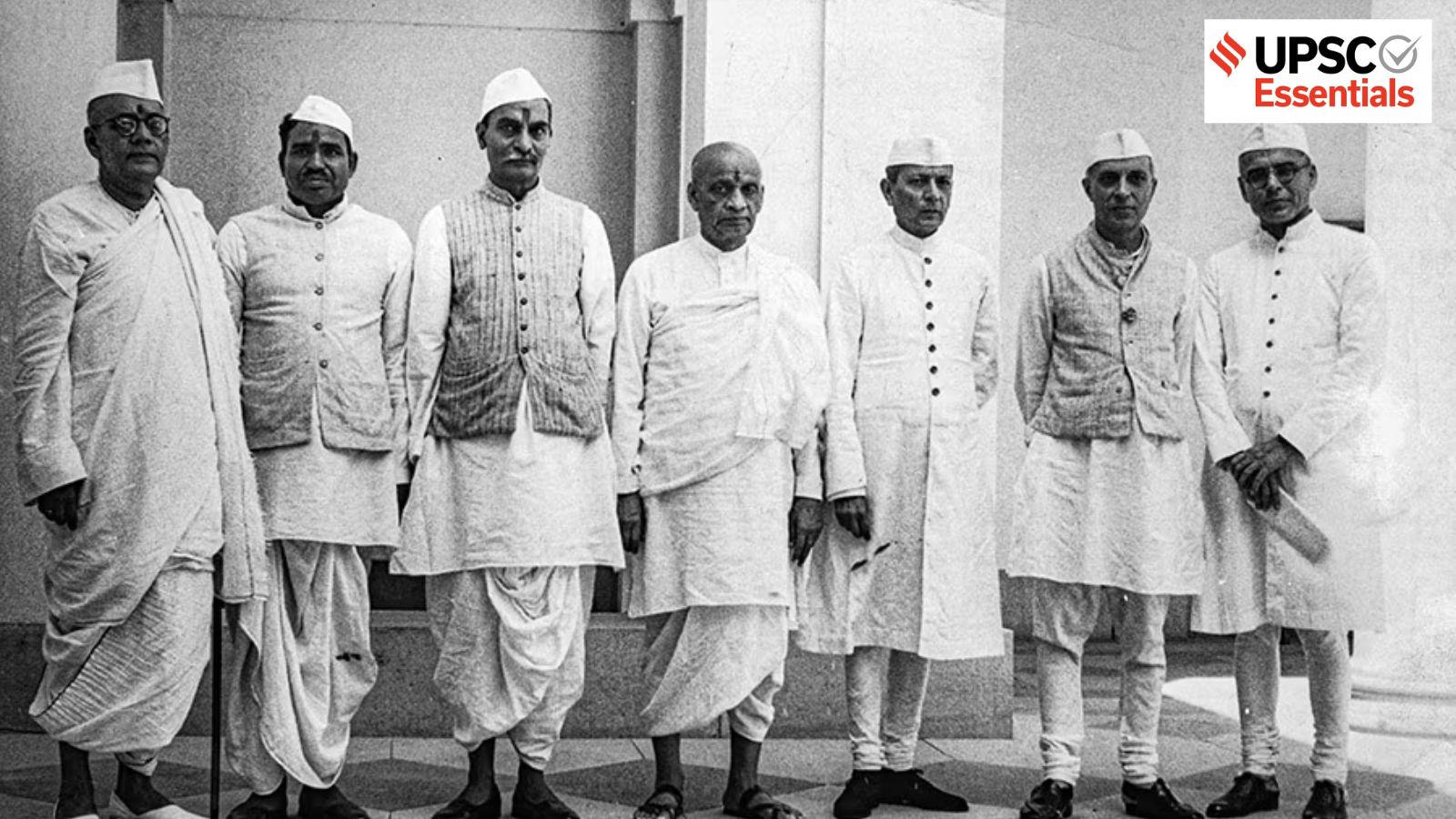

Photograph that documents the Partition. (Courtesy: the Partition Museum, Amritsar)

Jinnah’s leadership became increasingly authoritative, consolidating his control over the League’s provincial branches. This centralisation of power led to the marginalisation of regional leaders like A.K. Fazlul Huq in Bengal and Sir Sikander Hyat Khan in Punjab, who resisted Jinnah’s dominance. The League’s successful mass mobilisation campaigns in provinces like Bengal and Punjab were crucial in establishing Pakistan as an ideological symbol of Muslim solidarity, transcending class and regional divisions.

The electoral victory and the mandate for partition

The Muslim League’s mass mobilisation efforts culminated in the 1946 elections, which were portrayed as a plebiscite for Pakistan. The Muslim League’s sweeping victories in Muslim-majority provinces, particularly in Bengal and Punjab, solidified its position as the sole representative of Indian Muslims. In Bengal, the Muslim League won 93 per cent of Muslim votes (as mentioned in the book From Plassey To Partition And After by Sekhar Bandyopadhyaya), while in Punjab, it gained significant ground despite the opposition from the Unionist Party.

The Congress also secured a popular mandate, winning majorities in most provinces except Bengal, Sind, and Punjab. The 1946 elections marginalised other political parties, including the Communist Party, Hindu Mahasabha, and Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s All India Scheduled Castes Federation. The election results were interpreted as a popular endorsement of the Muslim League’s demand for Pakistan, and set the stage for the eventual partition.

In late 1946, British Prime Minister Clement Attlee recognised the untenable nature of continuing British rule in India through coercion. He cited several factors: the lack of sufficient administrative machinery, military commitments elsewhere, opposition within the Labour Party, questionable loyalty among Indian troops, and the reluctance of British forces to serve in India.

Global opinion and concerns within the United Nations further complicated the situation. Attlee’s government understood that the colonial rule could not be sustained, leading to a policy shift towards a graceful withdrawal. This was reflected in the actions of early 1946, including the announcement of the Cabinet Mission to India, which was intended to set up the constitutional framework for transferring power. While a phased withdrawal plan and a time limit on British rule were proposed, these were not fully accepted. Attlee’s approach underscored the inevitability of British departure, marking a significant shift in imperial policy towards India.

The Cabinet Mission

In 1946, the British government sent the Cabinet Mission to India to negotiate the terms of Independence. The proposal of the Mission under Pethick-Lawrence, Strafford Cripps, and AV Alexander, alongside then Viceroy Wavell rejected the idea of a sovereign Pakistan, but offered a compromise in the form of a loose federal structure with groupings of provinces. This structure would allow provinces to opt out of groups after 10 years but not from the Union.

The Mission’s goal was to grant independence, either within or outside the British Commonwealth, based on the Indian people’s choice. However, the Cabinet Mission’s plan failed to reconcile the contradictory demands of the Congress and the Muslim League. While the Muslim League insisted on the formation of Pakistan, Congress demanded complete independence for a united India.

The Mission’s rejection of a sovereign Pakistan led to further polarisation, with both parties becoming increasingly intolerant of each other’s agendas. The Mission’s failure to secure a consensus further hastened the inevitability of partition, as the political situation in India became increasingly volatile.

By the time Louis Mountbatten arrived in India, the idea of granting freedom with partition had already gained substantial acceptance. An innovative suggestion by V.P. Menon proposed the immediate transfer of power based on dominion status, which included the right to secede. This approach negated the need for a prolonged wait for consensus in the Constituent Assembly on a new political structure.

The Mountbatten plan and the partition of India

The Mountbatten Plan, announced on June 3, 1947, outlined several key points. The legislative assemblies of Punjab and Bengal were to meet in separate groups of Hindus and Muslims to vote on partition. If a simple majority in either group voted in favour of partition, the respective provinces would be divided. In the event of partition, two dominions and two constituent assemblies would be established. Sindh was allowed to make its own decision, and referendums were to be held in the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) and the Sylhet district of Bengal to determine their fate.

The Mountbatten Plan essentially conceded the Muslim League’s demand for Pakistan while attempting to retain as much unity as possible. On July 5, 1947, the British Parliament passed the Indian Independence Act, based on the Mountbatten Plan, and it received royal assent on July 18, 1947. The Act was implemented on August 15, 1947.

The Indian Independence Act 1947

The Indian Independence Act provided for the creation of two independent dominions, India and Pakistan, effective from August 15, 1947. Each dominion was to have a Governor-General responsible for the effective operation of the Act. The Constituent Assembly of each dominion was to exercise legislative powers, and the existing Central Legislative Assembly and the Council of States were to be automatically dissolved. Until a new constitution was adopted by each dominion, the governments were to function according to the Government of India Act, 1935.

As per the Indian Independence Act, 1947, Pakistan became independent on August 14, 1947, while India gained its freedom on August 15, 1947. Muhammad Ali Jinnah was appointed the first Governor-General of Pakistan. In contrast, India requested Lord Mountbatten to continue as its Governor-General, reflecting a symbolic continuation of British oversight during the transitional period.

The partition led to massive population exchanges, communal violence, and a humanitarian crisis, as millions of Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs found themselves on the wrong side of the newly drawn borders. The division of assets, including the military, civil services, and infrastructure, further complicated the process.

Post Read Question

Discuss the causes, consequences, and aftermath of the partition.

How did partition affect society and politics of India?

The speedy events under Mountbatten fail to arrange the details of partition and prevent the partition massacre. Comment.

Discuss the circumstances that forced Congress to accept the partition of India.

(Rahul Ranjan is pursuing his PhD in history from MSBU.)

Subscribe to our UPSC newsletter and stay updated with the news cues from the past week.

Stay updated with the latest UPSC articles by joining our Telegram channel – Indian Express UPSC Hub, and follow us on Instagram and X.

Share your thoughts and ideas on UPSC Special articles with ashiya.parveen@indianexpress.com.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nC4ckaj-dJI?si=HiDRY3KyDJMEoY0v&w=560&h=315